By Kaleb Nygaard

From evenings as the haute cuisine home chef, to the extra early arrival time at the airport, to the three days dedicated to drilling before each FOMC press conference, Janet Yellen is, at heart, an eager and anxious preparer. Her time management and attention to detail manifested in her college days with a series of lecture notes from Nobel prize winning professor James Tobin’s class that were so useful to other students many had them bound and one called them “the Old and New Testament for Yale PhD students.”

Retirement from public service, forced upon her by Trump’s unceremonious refusal to reappoint her to the head of the Federal Reserve Board, allowed her to settle back into a good rhythm of preparation. Despite prodding from new colleagues at the Brookings Institution and the example of her three Fed Chair predecessors, Yellen had no interest in writing a memoir. In Fall 2020, Biden would open the door to an entire new section in her life’s work.

Although she originally rebuffed the President-elect, Yellen’s family convinced her to accept his invitation to serve as the 78th Treasury Secretary, the first woman to hold the position in the nation’s history. It made her the first person to have held the nation’s top three economic policy positions: (a) CEA Chair, (b) Fed Chair, (c) Treasury Secretary. And she had already been the first woman to not only head the Federal Reserve Board but also the San Francisco Fed. This was another “first” in a career full of “firsts” for Yellen. Recognizing this, in 2017, three years before the cabinet position invitation, Time had put her on the cover of its special issue under the headline “Firsts.” Equally impressive, as Hilsenrath notes, “she [is] the longest-serving senior economic adviser of her generation, putting in more years in top policy roles than any person since Greenspan.”

Demands on her time increased exponentially. Gone were the retirement days of enjoying a full year preparing for big speeches. As she began service as the nation’s finance leader, mostly on Zoom as COVID-19 continued to wreak havoc on in-person work, Yellen had to manage a $1.9 trillion stimulus program and an economy simultaneously recovering and still reeling from the pandemic. At the beginning of her second year on the job, Russia invaded Ukraine and the US Treasury announced a series of escalating economic sanctions.

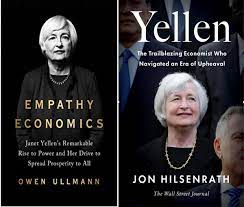

Despite both the preciously high value Yellen places on her time and the unending amount of work being asked of her in her new role, Yellen set aside dozens of hours to speak with two very different journalists during her first year as Treasury Secretary. Those interviews, as well as many others, often recommended directly by Yellen, make up the source material for two new biographies: Yellen: The Trailblazing Economist Who Navigated an Era of Upheaval by Jon Hilsenrath and Empathy Economics: Janet Yellen’s Remarkable Rise to Power and Her Drive to Spread Prosperity to All by Owen Ullmann.

Hilsenrath, a veteran reporter of the Wall Street Journal, where he has covered financial crises and the Fed for more than two and a half decades, frames the book as a love story of two marriages, one of Yellen to her Nobel prize winning husband George Akerlof and the other of “a market economy to democratic government.” Months before the book was released, Hilsenrath’s publisher posted two working titles to its website: the one they ultimately used and Janet and George: How Janet Yellen and George Akerlof, America’s Most Unlikely Power Couple, Navigated an Era of Economic Storms.

The latter is more accurate to the spirit and goal of the book. Too often biographies map a single hero’s quest to the top of their field. Hilsenrath demonstrates that we can’t separate the hero from the incredibly important relationships in her life. The chapters alternate between Akerlof and Yellen with prose that flows at a comfortable clip. Hilsenrath devotes a full chapter to their son, Robert, who is an accomplished behavioral economist in his own right. Their family dynamic is as nerdy as one would expect (hope). Indeed, the ideal Yellen/Akerlof family vacation is a beach resort with an extra suitcase filled with books, mornings spent reading on their own, and afternoons spent together eating good food and discussing what they’ve read.

Hilsenrath illuminates a family that cares deeply about the plight of the unemployed and the failures of the economics field and policy makers to create a more equitable society. Yet he also lets Yellen’s inner “Brooklyn upbringing” with all the “curses and colorful hyperbole” that come with it come through. These moments are often framed within boundaries of “righteous anger” and “moral passion.” But not always: Hilsenrath mentions that Yellen “surprised Fed staff with a feistiness and focus that rubbed some of them the wrong way.”

Ullmann, a former editor at USA Today, tells the story of Yellen’s life via extended quotations from family members, close friends, and people that admire her work. From the chapter titles and epigraphs to the framing of the narrative the book feels apologetic at best and hagiographic at worst. His underpinning thesis that Yellen is an empathetic person is unnecessarily overplayed given the arch of her career.

When not using block quotes to describe Yellen’s accomplishments, Ullmann highlights a few moments that may surprise Fed watchers. He claims that Raphael Bostic, President of the Atlanta Fed, was appointed “on the strength of her recommendation.” He also says as Treasury Secretary, Yellen not only argued against the nomination of Sarah Bloom Raskin for Fed Vice Chair for Supervision, but that she felt that Raskin “had been a weak member of the Fed Board…when they served together.”

A heavy hand in these two important personnel moments would be important additions to the cannon narrative. But Ullmann also made claims about Yellen’s desire to cut the American Rescue Plan by a third, which when Yellen publicly denied, he was forced to remove from the final version of the book. And regarding a hypothetical world where Yellen was still Fed Chair, Ullmann states as fact that Yellen would have raised rates more aggressively post-pandemic than Chair Powell actually did, without quote or citation, a claim that is difficult to swallow as unquestioned truth. These examples cast a dark shadow of doubt on the portions of the book that are not in direct quotes.

In closing, a few thoughts on reading the biography of a sitting Treasury Secretary, an important job at any time, a history-defining one at this time. Hilsenrath astutely notes that “Yellen had started the millennium an accomplished economist, but by no measure a historic one.” These two books may be the definitive works on Yellen’s life for the foreseeable future, which is a shame. Her time as Treasury Secretary will certainly be more consequential than her time as Fed Chair. (Though I’d argue not as consequential as her entire time at the Fed, a subtle but important caveat given her warnings leading up to the global financial crisis, her instrumental role in pushing the Fed to adopt an inflation target, her role in opening the Fed up to hearing from employment activists, etc.). But for this to be true we’re still a year or two away from seeing where the situation with inflation and the Russian sanctions will settle.

Maybe Hilsenrath and Ullmann will get to add an extra chapter or two for the paperback editions of their books, which at least would go some way toward assessing Yellen’s Treasury tenure.

The importance of the remainder of Yellen’s time as Treasury Secretary to her policy legacy makes for more than enough of a reason that economists and historians would benefit from a memoir: an important part of history will be missing if we don’t have Yellen’s story in her own words.

Kaleb Nygaard is BEF History Fellow at the Wharton Initiative on Financial Policy and Regulation.