By Felix Nockher

The separation of ownership and control allows shareholders to diversify their portfolios and firms to undertake value generating projects regardless of their level of idiosyncratic risk. However, the universal push for diversification often means that shareholders do not bear sufficient risk to incentivize them to monitor the firms in their portfolios. As a result, the managers running the firms on behalf of diversified shareholders may pursue private benefits at the expense of shareholder value.

The corporate governance literature generally focuses on those institutional investors that own the largest stakes in firms (so-called “blockholders”) as potential monitors of management. However, this focus disregards the effect of diversification. In practice, big blockholders, like BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street often hold large stakes in thousands of firms, making them highly-diversified and—as argued by the literature on common ownership—disinclined to monitor.

In contrast, there exists surprisingly little work investigating the monitoring value of smaller but undiversified institutional investors; investors that, through their concentrated bets, have a lot to gain from their monitoring efforts. In my research, I help fill this gap. In a new paper, I investigate institutional investors that have large proportions of their portfolio allocated to a firm, which I term high “Portfolio at Risk” (PAR) institutions.

I provide three key findings. First, I use textual analysis to measure shareholder engagement of institutional investors in the transcripts of corporate conference calls. I document a positive relationship between higher PAR and the engagement of high-PAR institutions. Yet, I do not find such a relationship for larger ownership stakes and the engagement of blockholders. This finding indicates that higher PAR (i.e., lower diversification) is a key determinant for institutional shareholder engagement and accordingly that high-PAR investors are important corporate monitors.

Second, I analyze 150,000 firm-quarter observations for the relation between high-PAR institutional investors and firm performance. I find that an increase in PAR by a firm’s top five PAR institutional investors is on average associated with an economically meaningful increase in operating profits and market valuations of $34mm and $731mm. This finding is consistent with high-PAR institutional investors being effective corporate monitors, reducing agency problems, and subjecting management to heightened market discipline.

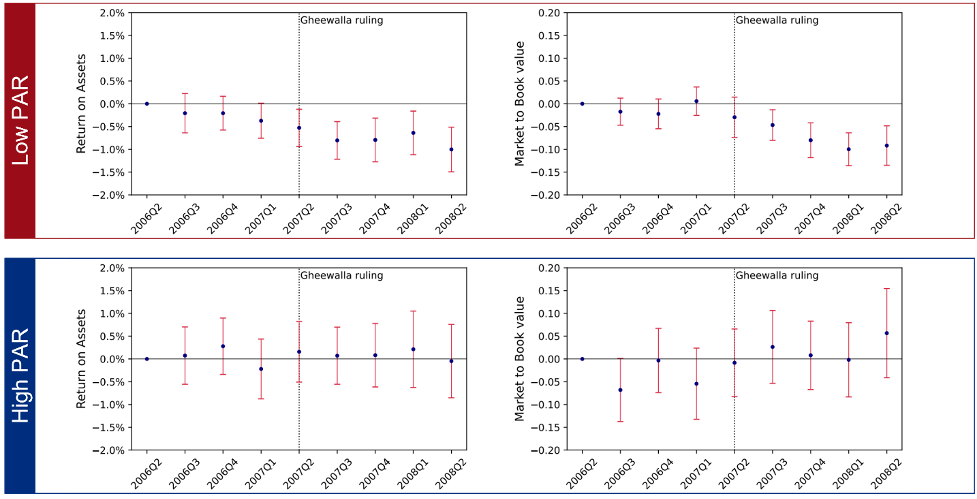

Third, I use a 2007 law change in Delaware that reduces the role that the monitoring by creditors (i.e., banks, bondholders, etc.) plays for firms (the “Gheewalla ruling”). After the Gheewalla ruling, I find a decline in profits and valuations for firms in Delaware compared to firms in other states. However, as shown in Figure 1, this result holds only in the subset comparing Delaware and non-Delaware firms that are owned by low-PAR investors. For firms owned by high-PAR investors there is no difference in performance between those in Delaware and those in other states. This finding corroborates the positive effect of high-PAR monitoring for firm performance. This is because only firms with low-PAR monitoring exhibit deteriorating performance in response to the reduction in creditor monitoring.

The importance of high-PAR investors for corporate monitoring provides a new perspective on governance. Extant policy work prominently focuses on index and mutual funds’ transparency vis-à-vis costs and portfolio holdings while mandating—and thus expecting—them to be informed monitors, e.g., through proxy-voting at shareholder meetings (17 CFR § 270.30b1-4). However, my findings show that it is not diversified institutional investors operating in an industry focused on cost-minimization that undertake performance-enhancing (but costly) monitoring efforts. Instead, it is high-PAR investors that undertake such performance-enhancing shareholder engagement, having a lot to gain from their monitoring efforts due to their concentrated bets. As a result, my findings suggest a refocus away from policies that impose governance efforts onto large asset managers toward policies that facilitate the monitoring efforts of smaller institutional investors. Eventually, academics, capital allocators (such as pension funds), and lawmakers must take into account the governance role of smaller but undiversified institutional investors. These undiversified institutions counter the rise in diversification-driven shareholder passivity, bringing about positive real economic effects.

Felix Nockher is a PhD Candidate in Finance at The Wharton School.

The views and ideas expressed in this post are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the Wharton School or the Wharton Initiative on Financial Policy and Regulation.